Chief Billy Assu was always ahead of his time.

The progressive leader of the Cape Mudge First Nation not only ensured a residential school was never built in his community but, under his leadership, the Cape Mudge Village was the first area on Quadra Island to have running water, electricity and indoor plumbing.

“He was really progressive and that’s really reflected in this centre,” says Jodi Simkin, the executive director of the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre on Quadra Island.

It’s at this centre that an exhibit dedicated to the life and times of Chief Billy Assu will open in the later part of September.

The opening ceremony was previously scheduled for Aug. 1 but was postponed following the July death of Assu’s grandson, Chief Donald Assu, who was also president of the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre.

The new date is expected to coincide with the return of an integral piece of the exhibit – two of Chief Billy Assu’s house poles from a museum in Ottawa.

In the meantime, Assu’s great-grandson, Brad Assu, has been carving replicas of the poles at the request of his father, the late Chief Donald Assu.

The poles are just two of 13 pieces that make up the exhibit dedicated to a chief Simkin describes as “very popular” and who served for 60 years before his death in February, 1965.

Another key piece of the exhibit is the chilkat robe which was woven by Mary Hunt. It has travelled across the country and will be on loan to Nuyumbalees for one year before it will move on to Alert Bay and then return to the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Que.

Simkin says in total 117 pieces of his belongings, such as art and potlatch regalia, were confiscated, but through negotiations Nuyumbalees has managed to return some of those to the centre.

It’s a practice that is at the heart of Nuyumbalees.

“It really started in the mid 1960s when Chief James Sewid called all the chiefs together and wanted to negotiate to get all the stuff that was confiscated during the anti-potlatch era,” says Rod Naknakim, vice-president of the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre. “He had seen a lot of it on display in museums in Ottawa and heard a lot wasn’t on display.”

So negotiations began and Sewid cut a cheque for more than $1,000 to have the items returned. The condition was, it would have to go to a museum rather than to all of the different families that were laying claim to the items which included masks, rattles, regalia and other ceremonial items.

As Cape Mudge had the largest piece of land available, all of the chiefs supported, in principle, building a museum there as well as a second museum in Alert Bay which would become the U’mista Cultural Centre.

Nuyumbalees opened with a great ceremony in 1979, followed by U’mista in 1980.

“It was the first of its kind in Canada designated to a repatriated collection,” says Simkin who describes repatriation as the transfer of ownership to the museum to hold, care and entrust for the families.

It’s what makes the Nuyumbalees Centre unique.

“What makes this different is every piece in the collection is intimate to the community, every piece has a connection to a family,” Simkin says. “In the last year and a half we’ve worked towards expanding the interpretation of our collection so we can enhance the visitors’ experience. That’s enhancement when we’re able to bring the pieces back to the community.”

To that end, Simkin says the work is never done and the centre is always working to recover pieces to add to the collection which currently stands at about 500 pieces, including 16 totem poles or welcome poles.

The two upper floors of the centre focus on a collection of potlatch items from the years 1884-1951, when the anti-potlatch laws were in effect, while the lower floor is full of pre-contact stone tools and other donated items.

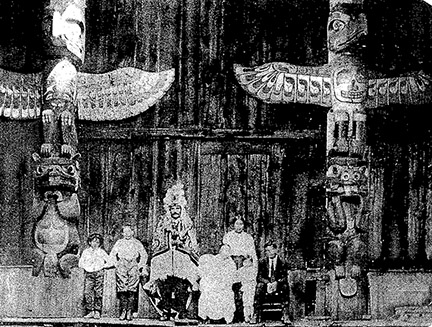

Chief Billy Assu, centre, dons the chilkat robe while standing in front of his house poles which will all be featured in a new exhibit at the Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre on Quadra Island.

Simkin says the pieces on display at the centre come back in a variety of ways – through long-term loans with other museums or through the repatriation process which can be lengthy and requires a lot of paperwork.

“We’re always looking for other pieces to fill in the collection,” Simkin says. “We did a survey of the community and most said that the most important function of the museum is the return of pieces from the potlatch collection. It remains considerably relevant to the community.”

And to other parts of the world as well.

While many of the visitors to the centre are from the local area, Simkin says they also see quite a few international and American tourists drop by.

On average, the centre greets 6,000 visitors a year, but last year those numbers were blown out of the water when 4,200 people came to Nuyumbalees for a Canada Day celebration – hospitality not seen on that same scale since the Chief Billy Assu potlatch days.

But despite all of the centre’s success, Simkin says the fact items of Assu’s were recently found in Zurich, Switzerland and in Vancouver, shows there’s more work to be done and that work is central to the sharing of the story.

“Thirty-five, thirty-six years after it opened its doors, the arrival of each new piece enhances the story and the community is re-energized after each new piece is brought in,” Simkin says. “Daycares and youth groups come to see the new items and hear the story and learn the history. It’s tremendous to see our efforts foster the continual revolution of the story.”

The Nuyumbalees Cultural Centre is open Monday through Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. until Sept. 29. Winter hours are in effect from Sept. 29 to May 1 when Nuyumbalees will be open Thursday, Friday and Saturday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.