High school teacher Tylere Couture took an interesting path to the classroom

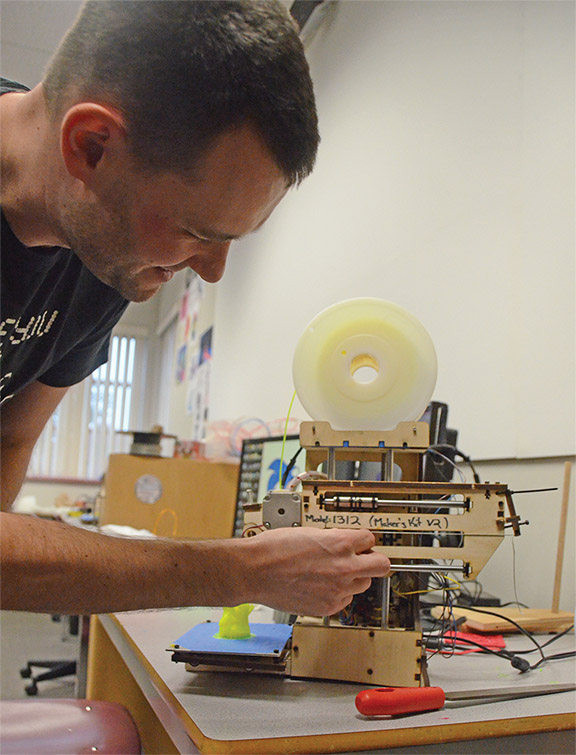

“This is Scribbles,” says the excited, energetic young teacher excitedly showing off a machine of some kind, seemingly built with bits of wood, with a spool of yellow plastic wire perched on the top and what looks at first glance, to be a blob of melted yellow plastic below it. The teacher is Timberline Secondary’s Tylere Couture. The machine is a 3D printer.

I’m looking at the machine after standing up from my chair at the Oculus Rift – the virtual reality contraption that just took me on a roller coaster ride around a fictional living room that I’m not hesitant to admit, made my stomach turn a bit.

Above me is a three-foot tall statue of Darth Vader on a shelf, overlooking a room of computer screens. And I’m talking to a man who graduated from this very school 17 years ago and is now teaching its computer programming, digital photography and digital art and design programs. This, after his time as a laser physicist in Vancouver and civilian/military liaison in Afghanistan with the Canadian Armed Forces, who happens to have a master’s degree in Human Security and Peacekeeping.

Wait, what? Yeah, let’s go back to high school graduation and start this story, shall we?

“After I graduated, I moved to Vancouver with my then girlfriend, now wife, to go to school. She went to Langara; I went to UBC to study physics and chemistry,” he says, simply enough.

Like many who go off to post secondary, however, he wasn’t really sure what he was going to do. Upon looking around at some options, he began thinking seriously about a military career – as a medical officer.

“But I had no idea what military life was like, so I joined the closest thing I could get without signing on the dotted line with a massive commitment, which was joining up with the Reserve Medical Unit as an administration officer.”

While he was doing that, he says, he also, “kind of fell ass-backwards into a job studying holograms,” using his chemistry and physics education while he finished his degree.

He continued on with the Reserves, and after he graduated, he was working full-time as a laser physicist – yes, that’s an actual thing – and he was trying to figure out how to also get some use out of his military training.

He happened across an organization within the military called CIMIC – Civil-Military Cooperation – which selected reservists from all different trades and skill sets and used them to liaise with civilian populations in areas where the Canadian Armed Forces had operations.

And Afghanistan popped up on his radar.

But he didn’t know anything about Afghanistan. So he started doing some reading, “and becoming more and more ashamed of myself for not knowing anything about this place, which had one of the highest maternal and infant mortality rates in the world.”

And his wife was pregnant. He knew he needed to go help in whatever way he could, because it was only luck that his daughter was to be born in Canada.

He resigned from his laser physics job, went to Edmonton for a year for training, and was off to Kandahar.

“I was appointed the team leader for Kandahar City,” he says. “I ended up being the main military liaison with the mayor of Kandahar City at the time. My job was to say, ‘okay how can we – as NATO, as an international force – help you?’”

As part of his lead-up to deployment, Couture had taught himself Pashto – one of the languages spoken in Afghanistan. This was no easy feat, because it was before resources were widely available to be able to do such a thing, but he credits that work with much of the his success in his role.

“That was probably the most important thing I did to build relationships in Kandahar – which was my job,” he says, recounting numerous times where, “the crappy little bit of the language I had, cracked through the shell of these people and enabled me to develop great relationships.”

At the end of his tour, he says, he came back, “and the deal I had with my wife was that I could go to Afghanistan, if when I came back, we could move back to Campbell River. But there weren’t – and although I haven’t looked into it, there probably still aren’t – a ton of businesses in Campbell River hiring either laser physicists or Afghani liaisons.”

So he went back to UBC to get a teaching certificate, they moved back to Campbell River, and he applied to become a teacher in School District 72.

He became a Teacher On Call (TOC) with both SD72 (Campbell River) and SD71 (Comox Valley), but he was still doing physics work on contract for his old employer based in Vancouver, and was working at the clinic at CFB Comox, so he was sort of too busy to accept teaching calls when they came. And so he was removed from the TOC list.

He wanted to be a teacher, but he “wasn’t really interested” in sitting around and waiting for calls to fill in for someone else, so he dropped teaching and went back to school, yet again, at Royal Roads University.

During his completion of that program – a master’s degree in Human Security and Peacebuilding – he ended up back in Afghanistan again, completing his RRU thesis on an under-the-radar school for girls.

“It was probably the most amazing thing I’d ever seen. It was this nondescript building – gated like everything there, you wouldn’t even notice it if you were walking by – and you open the gates and in every corner of the compound, in every nook and cranny, there were young women – girls, really – taking classes in English, computer skills, they had all sorts of stuff, and I was totally blown away.”

It wasn’t illegal, per se, for this place to exist. It was, however, extremely dangerous.

After completing his graduate work while volunteering in the school – he returned to Campbell River. He signed back up for the TOC list, deciding to give this teaching thing another go.

While he was subbing this time around, he was chatting with other teachers, making connections, and actually getting semi-regular classroom work.

Then at the start of the 2014 school year, while he was prepping for the math class he was supposed to be filling on a temporary basis at Timberline, it was mentioned to him that the computer teacher had retired late in the previous year, and they were having trouble filling that role.

“And I said, ‘Hey, I know a bit about computers,’” he laughs. “And I’ve been full-time teaching computers here ever since.”

Never being completely content with what he’s doing at any given time – “as you can tell, I’ve bounced around a lot with what I’ve done,” he says – and wanting to push himself and his career as far as he can, he’s since added another passion to his teaching schedule, as well.

He recently presented his pitch to the SD72 Board of Education to begin teaching Philosophy 12 next school year, following from the Philosophy 11 course he began this past year. Philosophical discussions and theories, he says, open the mind and get people thinking critically about the world around them.

Fittingly, for someone of his background of international aid and social justice, one of his personal favourite philosophical scenarios is called, “The Drowning Child.”

“If you’re driving home today”, Couture asks, “and you hear a child calling from a creek likely drowning – maybe your window is down, so you heard their struggle – do you pull over and run to save the child?”

“Of course you do,” I say.

“Okay”, he says, “but what if you’re in a neighbourhood where the chances are good your car will be stolen by the time you get back to it?”

“Of course you still try to save the child,” I say.

“Okay”, he continues, “what if there are a bunch of other people, already standing around watching the child drown, and nobody is doing anything?”

“Obviously, that’s irrelevant,” I say. “You still try to save the child.”

“Okay, but what if there’s a pretty good chance the child will still die anyway, despite your efforts?”

“Also irrelevant,” I say.

“So what you’ve admitted”, Couture points out, “is that you would do your part to save a child – who may die anyway, despite your efforts – even though other people also have the opportunity to try to save the child and it may cost you, say, $1,000?”

“Yes.”

And that’s the answer most people give to that scenario. But children die all over the world every day, and we know about them, and we can help them, but we don’t.

It’s an internal struggle Couture lives with every day.

“Do I really need that new computer?” he asks rhetorically, sighing. “Maybe not.”

His wife, a local potter, donates 20 per cent of the sales of her work to the charity Canadian Women for Women in Afghanistan as a result of their discussions around the “Drowning Child” scenario, and Couture is doing his part to get more people thinking critically about the world, as well.

Meanwhile, he’ll be in his crazy, geeky classroom filled with 3D printers, a television that has a constant game of Tetris running, a computer in a fish tank and a remote controlled foam missile launcher on his desk to get students’ attention when he needs it, broadening the minds and educating of the youth of our community, while he waits for his next opportunity to go volunteer with that school in Afghanistan.