It was around midnight when the corporal came around to the barracks and ordered everyone out to the trench. For what felt like an hour the men huddled in the rain, wearing only their pajamas as planes roared overhead and explosions sounded in the distance.

“You never knew when one was coming down near you,” said Robert Walker.

Walker, now 94-years-old, joined the Canadian Air Force in 1944. At the time enlistment was mandatory and if you didn’t want to join the army you had to choose something else. Walker had heard about the troops sleeping in trenches filled with mud, so he decided to join the Air Force instead.

He initially trained as a pilot, in single engine Tiger Moths, but when he graduated to dual engine aircraft he wouldn’t get the hang of it. “I don’t know if it had something to do with me,” he said. “I had trouble getting both of the engines running the same speed.”

So Walker learned to navigate.

After completing training courses at stations across the country, he was called to duty while on his honeymoon in Quebec City. His new wife, Betty, went back to Courtenay, and Walker travelled to Halifax, where he boarded a ship to England. It was jam packed with military personnel.

“The room where I was sleeping, there was bunks in there, I think I was the top one. There was five bunks one on top of the other,” Walker said.

At one point the ship’s captain got word that there was an enemy submarine about 50 miles ahead, waiting for the ship. “They were going to sink us,” Walker remembers. “He turned 90 degrees south and then went along so far and then went back up again and got away from it.” Upon arrival in England, Walker continued his training at stations in Edinburgh and Glasgow before being stationed in Skipton-on-Swale.

“If you didn’t do a good job of it you never came back.”

His very first day at the base he witnessed a plane crash during takeoff. The wing caught, the plane tipped and there was a huge explosion. The only survivor was the rear gunner.

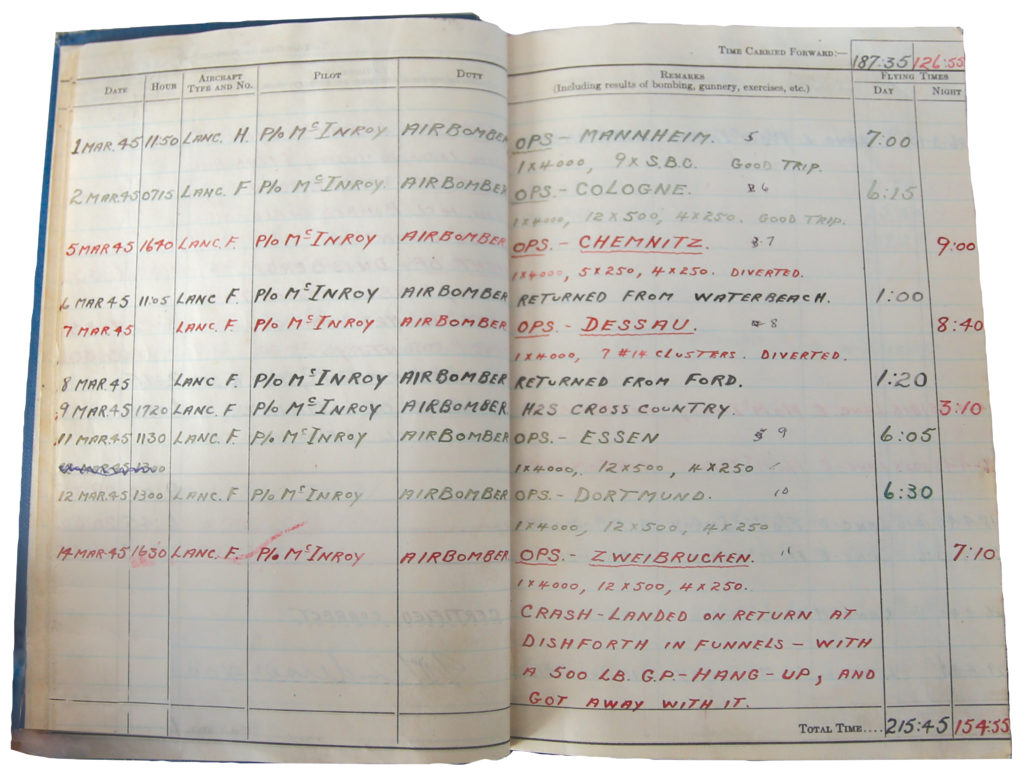

Walker flew with pilot McInroy. The crew of seven or eight was one of 15 stationed at Skipton at the time. Walker flew to Germany on a Lancaster to drop bombs 15 times between Feb. 1, 1945 and April 26, 1945, according to his flight log.

“I’m not supposed to have that,” he said. Walker was in a corporal’s office while the officer was processing the flight log books. The phone rang down the hall and the corporal left Walker alone in the office. “While he was gone I looked over the pile and I saw mine there, so I picked it up and stuck it in my pocket,” he said. After mixing up the table to cover up his theft, the corporal returned and had no idea. “I’ve had it all these years and I wasn’t supposed to,” he said.

All 15 crews flew out together. Two or three of them wouldn’t come back. “[We were] lucky to get back,” Walker said.

He never had to deploy a parachute, though they did have a few close calls. Walker remembers accidentally flying into enemy airspace when returning to base. The navigator made a mistake and suddenly there were anti-aircraft shots exploding behind them.

Walker said he jumped up to look behind them, through the dome in the ceiling of the aircraft, and he could see them coming. McInroy dove down 45 degrees and turned towards England.  “We got out of there in a hurry,” Walker said.

“We got out of there in a hurry,” Walker said.

Walker also remembers crash landing at the base with a live bomb on board. He said they couldn’t get rid of it, they kept trying until they ran out of fuel and ended up landing with it. Luckily it didn’t go off.

Before every trip off base, the crews gathered in a class room. “You never knew where you were going until you got there and then they would pull a map down,” he said. They would show the crews where they were going and the navigators would have to write down the directions.

Walker remembers the padre who lived on the base waving as the crews took off.

Walker still has some of the paperwork he did in his seat behind the pilot. There are sheets and sheets with rows and rows of figures, the only technology they had were little metal boxes that had the latitude and longitude running across the top. “It was busy,” he said. “If you didn’t do a good job of it you never came back.”

Walker’s daughter asked him is he was ever scared. Walker said he was too busy to be scared.

Walker was in Canada, waiting to be reassigned, when the war ended. He joined his wife on Vancouver Island, and started working again at the Royal Bank, the same business where he met his wife in the first place. He worked in Courtenay and Cumberland before moving to Campbell River.

At 94, Walker was only recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and he lives on his own in an apartment next to his daughter on their original Campbell River property.