This year, at least one local woman will say ‘I love you’ as often as she can

Only two-and-a-half short years ago, a then-34-year-old Kimberly Bennett was working away at her burgeoning career in auto insurance sales, living the typical life of a born-and-bred mid-Islander. She and her three-year-old daughter were a happy pair of ladies just making their way through the world as best they could. But on Mother’s Day of 2014, everything changed.

“I woke up at about 3 a.m. and I couldn’t see out of my right eye,” Bennett says. “I got out of bed, and thought, ‘did I just have a stroke?’” She decided that, no, she probably didn’t just have a stroke. She probably just slept wrong and some pressure was placed on a weird spot on her face or something. So she went back to bed.

But when she mentioned to it to her mom the next day, when she and her daughter went over for a nice Mother’s Day breakfast, she – as moms will do – made her go get checked out.

She went to the doctor, and was relieved, at first, to find out she was right about not having a stroke. And her optometrist said nothing was wrong with her eyes. And the ophthalmologist she saw said the same thing.

“But then the ophthalmologist started asking me these questions about whether I had any numbness or tingling in my hands and feet, which was something I’d been complaining about to my doctors for years, but they had always chalked it up to poor circulation or a pinched nerve – something normal,” Bennett says.

Once the ophthalmologist had her answers to those questions, she decided Bennett should probably have an MRI. “We had to rule out multiple sclerosis,” Bennett says. “We didn’t talk about what else it could be.”

But it wasn’t multiple sclerosis.

On Sept. 4, 2014, she found out what it was. The phone rang, and instead of being told over the phone, she was asked to come to her doctor’s office.

“I’ll never forget when he walked in the room. I could just tell by the look on his face that something was very wrong,” Bennett says. She tried to be casual, asking him as light-heartedly as she could muster, “So, what’s up, doc?” “But he just looked at me for a minute not saying anything. Then he just said ‘I’m sorry.’ Sorry for what?” Bennett asked. Since there is no easy way to tell someone they have a brain tumour, he just said it.

And then it was real. And that was the start of what her new life would become. Her life, for quite some time, became a series of tests and appointments with various specialists… and then more tests. And nothing was changing, “so they gave me the option to watch and wait or have a biopsy done, but surgery wasn’t an option because of the location of the tumour,” she says. “There was a greater risk than there was a reward, so to speak.”

“I wish people wouldn’t take life for granted. Love every second you’re awake, and just tell people you love them.”

Based on the size and density of the tumour, Bennett says, “they figured I’d had it a long time, but it was a slow-growing, non-aggressive form of brain cancer. But as a single mom, I couldn’t just watch and wait. I needed to know what I was up against.”

So she went across to Vancouver General Hospital for a biopsy. She was in there for three days after the biopsy was done. They can’t release you until they know you can balance and take care of yourself well enough not to stumble off a sidewalk into traffic, after all.

And they came home to wait for the results. These she got over the phone. She could have gone back over to find out in person what was going on, “but I didn’t want to make that trip again if I didn’t have to,” she says. She had planned for her mom to be at her side when she took the call, but when the phone rang, she answered it rather than letting it go to voicemail and calling back after her mom got there. So she was by herself.

“I’m really sorry to tell you that you have a Stage III brain tumour,” the voice on the other end of the line said. “That’s one stage below the worst it can get,” Bennett says. “Stage IV is, like, there’s no coming back.” So she asked about treatment options.

She’d have to head back over to Vancouver for seven weeks of radiation, five days a week, “and chemo every day,” she says. “It was pretty intense.”

Her mother brought her daughter over once early in her treatment, but that was the only time.

“It was so hard on everyone,” Bennett says. “Saying goodbye again…” she pauses to collect herself. “She didn’t understand. She was only four. That’s really, really hard for a little person to understand, and for myself to have to watch her leave, knowing I was staying … it was tough. So I asked my mom and dad not to bering her back until I could come back with them and start my new life.”

And when she got back to Campbell River, she found out exactly what that new life would entail. It was a life of five days of chemotherapy pills, followed by blood work to figure out what her next dose should be when it started 23 days later.

“I was so sick. I was puking and … just so tried,” Bennett says. “For six months it was all I could do to get up the stairs to the bathroom. I couldn’t eat because I had no appetite. I was about 130 lbs when I started treatment and at one point I was down to about 107.”

But now, a year out from that constant treatment – she still has to go in for periodic brain scans to see what’s happening in there and take some medication to keep side-effects of the disease under control – she’s back up to a normal weight, she’s got enough energy to keep up to her daughter most days, and she’s got a totally new outlook on life.

“It makes you appreciate the little things and the things that maybe you took for granted and never thought were important,” she says.

The taste of food.

Going for a walk beside the ocean.

Even just waking up in the morning.

“Unfortunately my memory sucks now,” she says with another light-hearted chuckle. She laughs pretty easily for someone who is talking about the negative effects of brain cancer. “I can remember the stupidest things from my childhood that have absolutely no meaning or relevance, but I can have a conversation with my boyfriend in the morning and forget having it by the time he gets home from work. My daughter says I have ‘remembery problems,’ which I totally do,” she says with another laugh.

The bad news is that probably won’t ever change. The good news, however, is also that it could never change.

The bad news is that probably won’t ever change. The good news, however, is also that it could never change.

“I’m fortunate that, because of the kind of cancer it is, it won’t metastasize outside my brain,” she says, but she’ll have it forever and she’ll have to keep checking in on it for the rest of her life.

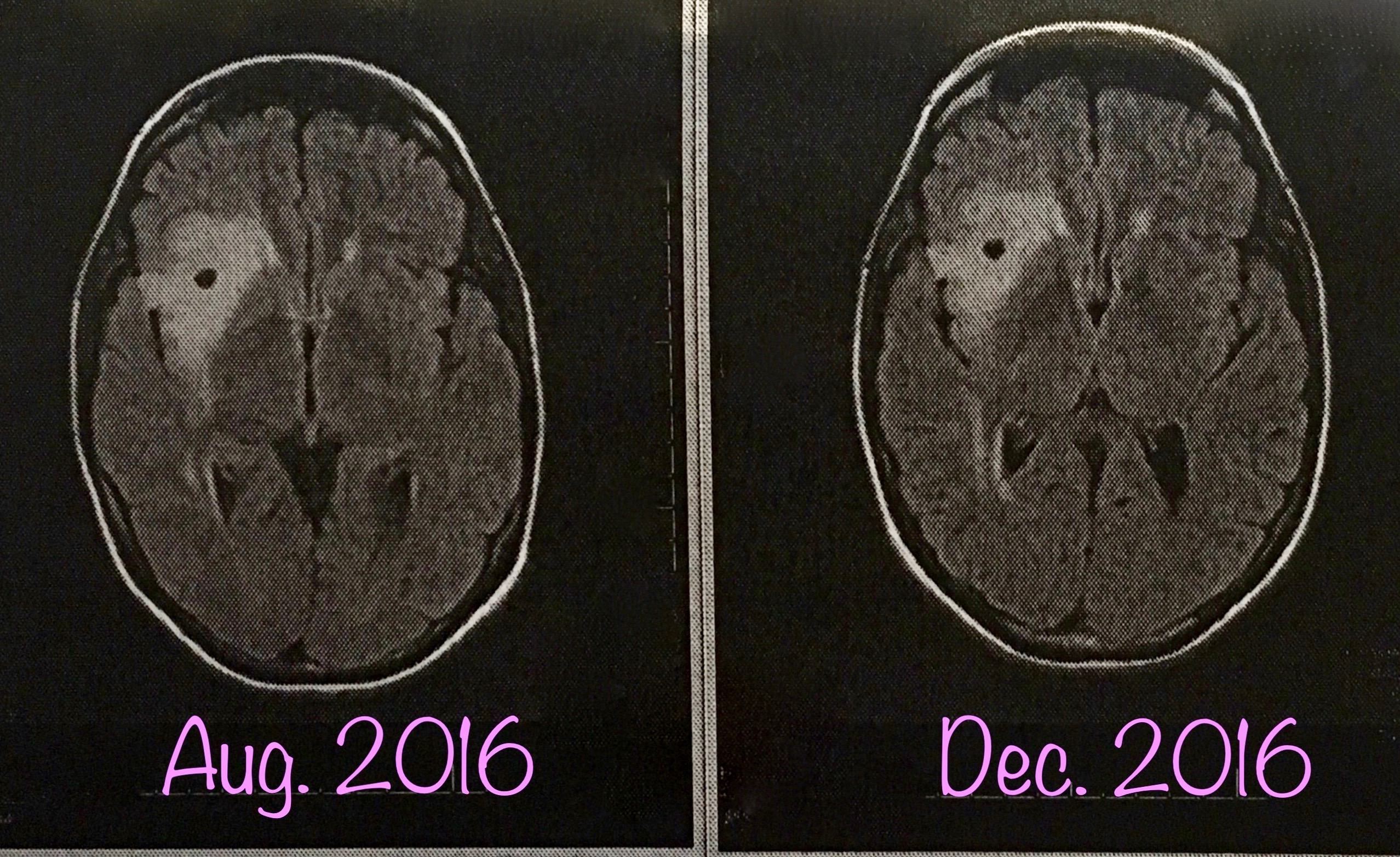

She goes for another scan every 12 weeks, and puts the image up on her fridge beside the first one from 2014 as a reminder that she’s still kicking this thing.

“I need that tangible proof,” she says. “It helps me stay positive.”

She gets a little stir crazy, she says, because she’s not able to pursue any sort of “competitive employment,” meaning she’ll never be able to go back to her old job – or hold any job for that matter. Probably ever.

“I’m a liability,” she admits. “My short-term memory is so bad that I just can’t reliably keep things in there. If you were to train me to do something, it’s possible it just wouldn’t stick.”

She also has some new dexterity issues. “I can’t even French braid my daughter’s hair anymore. I have to really concentrate on things that I used to be able to just do with my eyes closed – normal, everyday things like doing up the button on my pants. Tying shoes…” she trails off. But she does what she can to stay busy.

“At 34-years-old, to be told you’ll never go back to work…it’s tough. But, you know what? I get to spend that much more time with my daughter, and not knowing how much time I have left, it makes those hours – those minutes – so much more special.”

And so she volunteers as much as she can for her daughter’s school activities.

And she fundraises for cancer research.

Most importantly, though, she spends a lot of her time telling people she loves them.

“I don’t walk away from anybody I love without telling them that,” she says, choking up a bit – not for the first time during our discussion. “Because you just don’t know…today is a present and tomorrow is a gift you don’t know you’re going to get, so you have to tell those people you love them.”

And she wishes everyone would do that more.

“It shouldn’t take getting brain cancer for people do that,” she says, back to laughing again, somehow. “I wish people wouldn’t take life for granted. Love every second you’re awake, and just tell people you love them. Whether you say it once a day or 20 times a day, just tell them.

“And wake up every day, appreciating that. Appreciate that you woke up again.”

That’s what she’s going to do, at least.

And she’ll do it with a smile, and a laugh … and an “I love you.”